Eye care, glasses should be included in our social insurance scheme

I am one of the five members of my family who wear glasses. In my office, five out of my 11 staff members also wear glasses. With changing lifestyles at work and home, we have exposed ourselves to longer hours in front of electronic devices, which is affecting our eye health. This is something we are all familiar with.

Visiting eye clinics and optical shops once or twice a year have been important health priorities for me for the past 15 years. And it costs money. I am so grateful that my office has a policy where our employees are provided with a health package that includes eye care and glasses. This has reduced my and my team’s out-of-pocket spending and has improved our eye health.

But there are millions of people out there who do not have access to eye care and glasses. The demands for eye care services – including treatment for low vision and provision of glasses – are growing because of many factors. Life expectancy is increasing in Cambodia, with more people approaching the age of 60. Changing lifestyles have also caused an increase in demand for these services.

And if eye care and glasses are included in the national social insurance scheme, we could save thousands of people every year from avoidable blindness and vision impairment.

Are there any countries that provide free eye care?

Poor vision is a significant development and health challenge. The World Health Organisation estimated that 253 million people globally live with vision impairment. And the leading causes of vision impairment and blindness are cataract and uncorrected refractive error. There are a number of countries that provide free eye care to their people to address these emerging challenges.

In 2018, Rwanda was the first low-income country to provide free universal eye care to its 12 million people. It was estimated that a third of Rwandans had sight problems. In an ambitious project, the Rwandan government has partnered with Vision for a Nation to train more than 3,000 eye care nurses in the country.

Canada has implemented a robust eye care policy for years. This policy requires that the public health insurance covers medical payments for eye injury and diseases such as glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy and cataract. It also covers the associated costs of eye examinations, glasses and frames, contact lenses, and a portion of laser surgery costs for vision correction.

Some OECD countries, like the US, have implemented a vision insurance policy such as Vision Service Plan, UnitedHealthcare, Direct Vision, and EyeMed, which covers eye careassociated costs like eye examinations, lenses and glasses, new frames and surgery.

The status of eye health in Cambodia

A 2016 report of the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated Cambodia’s total health expenditure at about $1 billion in 2014. This same report stated that the three main sources of spending within the Cambodian health system were financed by out-of-pocket expenses, donor payments, and government expenditure.

Among the three, out-of-pocket costs tops the list. In 2014 alone, every Cambodian contributed an estimated $43 in out-of-pocket health spending. For people in rural Cambodia, spending on healthcare accounts for 11 per cent of their household expenditure, but that percentage rises to 20 per cent for the nation’s poorest households.

The 2019 Report of Cambodia’s National Rapid Assessment on Avoidable Blindness found that 92.2 per cent of all causes of blindness are avoidable, 80.9 per cent are treatable, and 5.9 per cent are preventable with primary eye care. It is unfortunate that nine out of 10 people who are blind or vision impaired don’t need to be.

WHO has estimated that the number of Cambodian people with diabetes would reach 317,000 by 2030, which means more people will experience vision impairment or loss.

The National Strategic Plan for Blindness Prevention and Control 2021-2030 aims to advocate for the inclusion of refraction services and provision of glasses into the national social insurance scheme, but it won’t go far without the support from decision makers and the insurance industry.

Potential benefits of having universal eye care in Cambodia?

A report of the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness indicates that 90 per cent of those suffering from vision loss live in low and middle-income countries. Women are 12 per cent more likely to have vision loss compared to men. This same report suggests free high quality cataract surgery has contributed to a 46 per cent increase in household income, and an 88 per cent increase in household expenditure per capita. Thisdemonstrates that in low and middle-income countries like Cambodia, good eye health can lead to better opportunities in terms of livelihood and income generation.

Despite these benefits to one’s quality of life, many people still delay or avoid updating their prescription glasses due to high out-of-pocket costs. The result is it hastens their vision loss.

Having access to universal free eye care and glasses will allow early detection of eye diseases, making interventions affordable. Out-of-pocket spending will be reduced, and people will have more resources to invest in their children’s education and wellbeing.

The annual productivity losses associated with vision impairment from uncorrected presbyopia and myopia alone have cost the world about $25.4 billion and $244 billion, respectively. With this policy intervention, Cambodia will be able to address these productivity losses and maintain its economic competitiveness.

Rwanda’s case gives us hopethat lower-middle-income countries like Cambodia can also achieve a strong eye health sector, backed by universal eye care for all citizens.

The clock is ticking. The inclusion of eye care and glasses in the national social insurance scheme will save thousands Cambodian people eachyear from avoidable blindness and vision impairment.

Tokyo Bak

Cambodia Country Manager

The Fred Hollows Foundation

The article was orginally published in Phnompenh Post

Related articles

7 Things My Dad Taught Me About Changing Lives

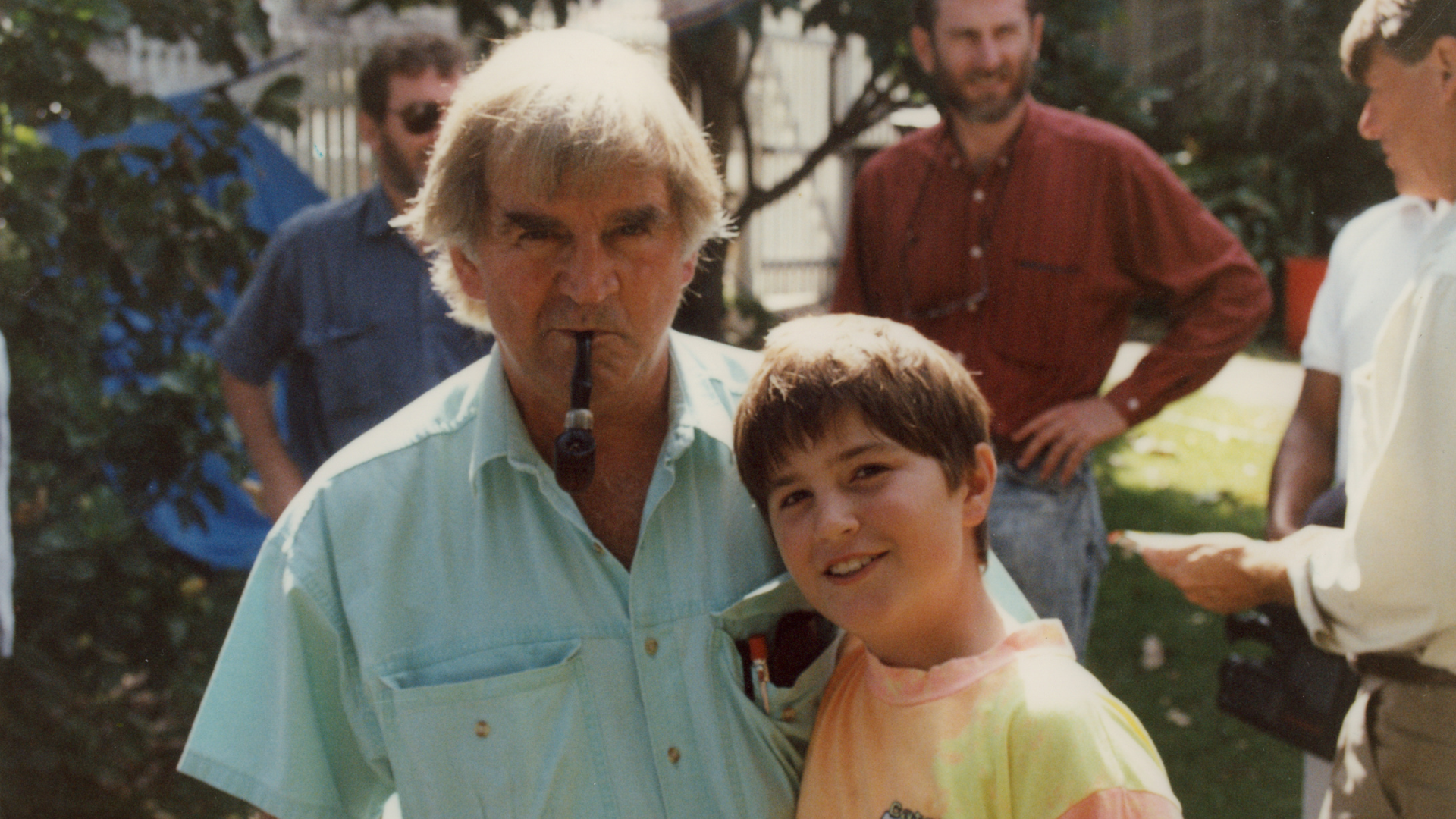

Michael Amendolia’s favourite photos of sight restored